Danau Tanu

“Racism” and “global citizenship” sound incompatible—like oil and water. This past year, however, we’ve been forced to acknowledge that systemic racism exists even within the “international school ecosystem,” to borrow AIELOC’s expression.

It exists even in international schools with a diverse student body. But how?

According to Nick, a North American teacher at an international school in Indonesia, it gets taught as part of the “hidden curriculum.”

“It’s what we say we teach, which I believe we believe in and we’re trying to do, but by the very makeup of the institution, we are teaching this hidden agenda,” Nick explained. “It’s not like anybody’s setting out to try to teach it, but it’s being taught because it’s our daily experience here.”

Pennies before rupiah

An alumna of Nick’s school believed the curriculum shaped the cultural hierarchy on campus. Lianne said, “I think because our teachers were mostly Americans, a lot of our study material was based out of the States. I learned what a penny was before I learned about the Indonesian rupiah!”

Lianne was referring to the math problems in her textbooks, which used currencies that were not used locally.

“And social studies was always about [western] history before world history,” Lianne added. Scientists and literary authors also mostly had English or other European names.

But it isn’t just about who or what is included in the textbooks. It is also about what is omitted.

Missing pieces

Large portions of the world do not appear in these textbooks. Or, if they do, it’s tokenistic.

By high school graduation, an international school student who grew up in Asia might have learnt about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and its role in the start of a major war between European powers. They might also be able to write essays on Medieval Europe and the European Renaissance.

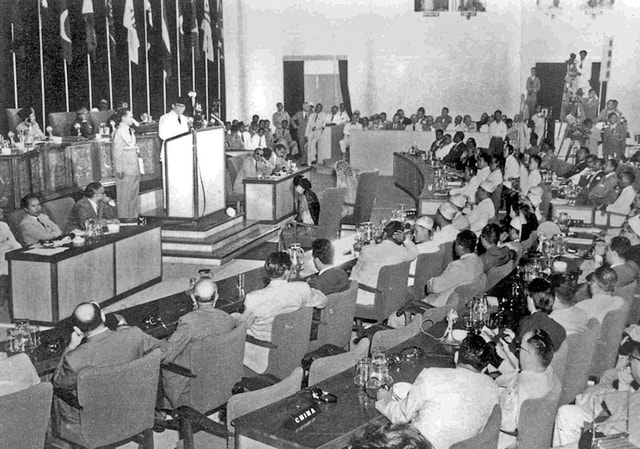

Yet, they might not know the significance of the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia when the heads of newly decolonized African and Asian states held a large-scale summit for the first time. They might know very little about Asian history and may not even have heard of the Ottoman Empire. It is also likely that they have never learnt about the legacies of colonialism in present-day political structures.

Students may be familiar with the European origins of “Roman numerals” but they might not have heard of the Indo-Arabic origins of the numbers they use daily.

After graduating, Lianne went on to study English literature in Australia. “Then I go to university,” she recalls, “and it’s like, ooh, colonization? Hmm, how come I didn’t study that at school? Duh, we were being colonized!” Lianne let out a laugh.

But it isn’t just about textbooks.

The operating system

“I honestly think that it was just the system,” Lianne offered. “It was the operating system of the school: the workbook, the teachers, and then most of the kids were of course American kids. It’s the oil kids, Mobile Oil, Castrol, right?”

Nick gave a more specific example. “For certainly the vast majority of our students,” he pointed out, “they see Indonesians in subservient positions—primarily drivers, nannies, maids, gardeners, secretaries, electricians, and what have you.”

The large number of local cleaning, gardening and security staff on campus generally remained nameless and faceless to students and teachers.

“How many Indonesians do they see in positions of power?” Nick asked. “They don’t, right?”

Most of the teachers were white, including Nick. At the time of my interview with him, all five of the leadership positions in the high school administration were filled by white men. This was despite the use of international recruitment processes in a female-dominated industry.

Token diversity?

Although there were some non-white educators at the school, this does not prove the absence of racial bias in the hiring process.

It is possible that some were hired because they fit the existing images or stereotypes of non-white educators. Around half of them taught languages other than English. Only two were Black: a male physical education teacher and a female guidance counselor.

While I had not given it much thought at the time, it was uncanny to hear Ryan Haynes, a counselor who works at another international school, say in an interview recently on The Global Chatter podcast that people often assume he’s a physical education teacher due to the stereotype of Black men as athletic. Haynes also noted that guidance counselors are sought after internationally.

Internalizing the structures

The racial composition of those in positions of authority does not go unnoticed by students.

Teachers like Nick could see the negative impact of the hidden curriculum on their own children who also attended the school. Nick, who was married to an Indonesian, observed that his seven-year-old, mixed-race daughter looked down on Indonesians.

A senior student at Nick’s school also shared a story that illustrates how students unknowingly absorb the racial biases of a hidden curriculum. “One of the things that I find really strange is,” said Tim, “when I’m here, most of the workers in McDonalds … in all these restaurants are Asian, and then going back to the States and having [to give] orders to someone who is white or Caucasian is really strange to me. It’s really weird. I don’t know why.”

Tim was not used to seeing white people in working class occupations serving others. He had expected them to be in positions of authority.

Enduring patterns

The demographic makeup of international schools has undergone major changes across the world over the past few decades. But little has changed in terms of the hidden curriculum. Nick and his students’ description of the school in 2009 closely echoed that of Lianne’s experience in the 1980s to 90s.

Today, the same stories are still being told in many places. Last year, the Organisation to Decolonise International Schools (ODIS) led by two recent graduates of international schools stated, “Many international school alumni have testified that their education was too Westernised and centred on white culture, history and achievements.”

This does not mean, however, that international schools have completely failed.

Although he was critical, Nick also said, “There’s no other school I wanna send my children to. I really believe that it’s an incredible [education] that we’re offering—the multiculturalism and all of those aspects that are powerful and good.”

But he added, “There is this dark underbelly that isn’t being addressed there. I think it poisons the system to some degree.”

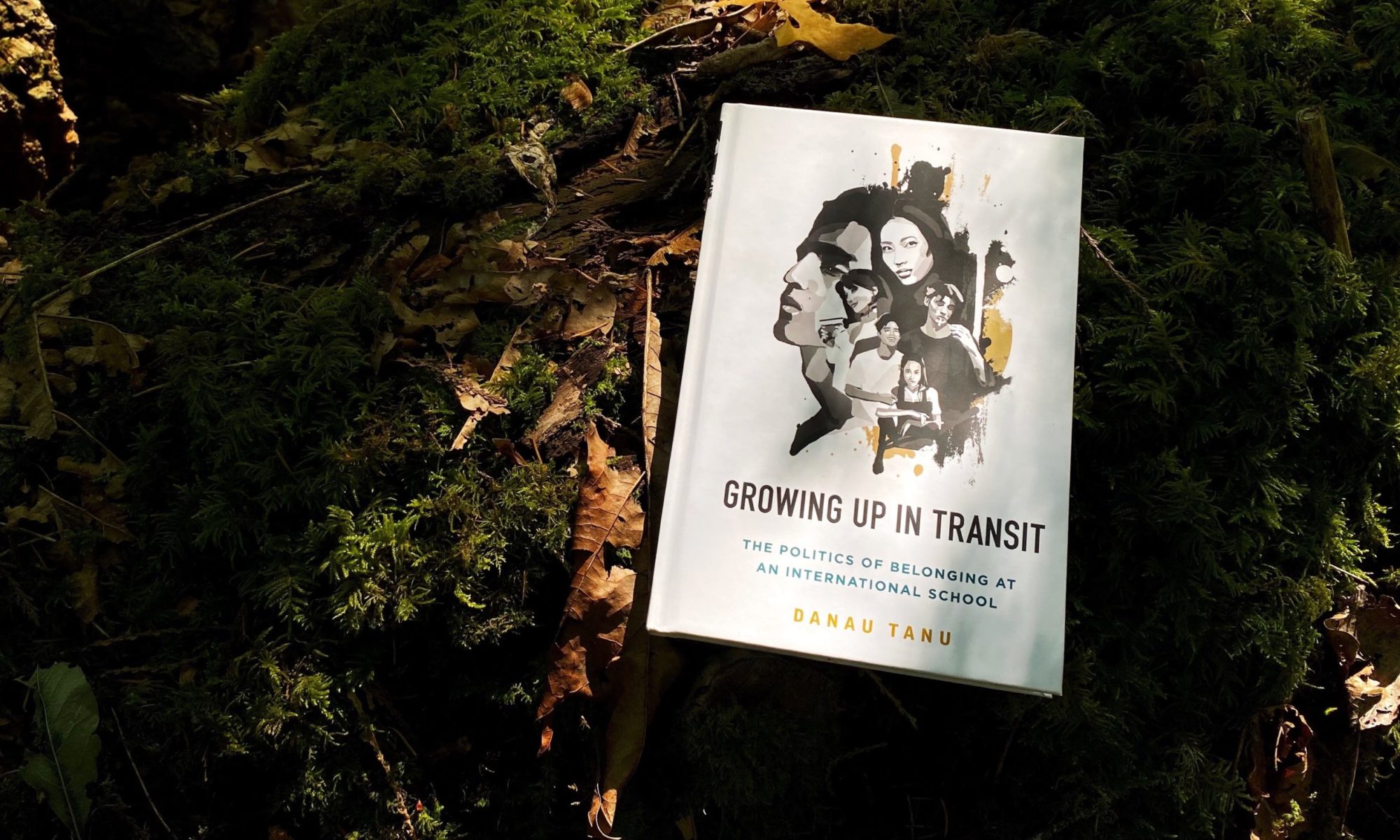

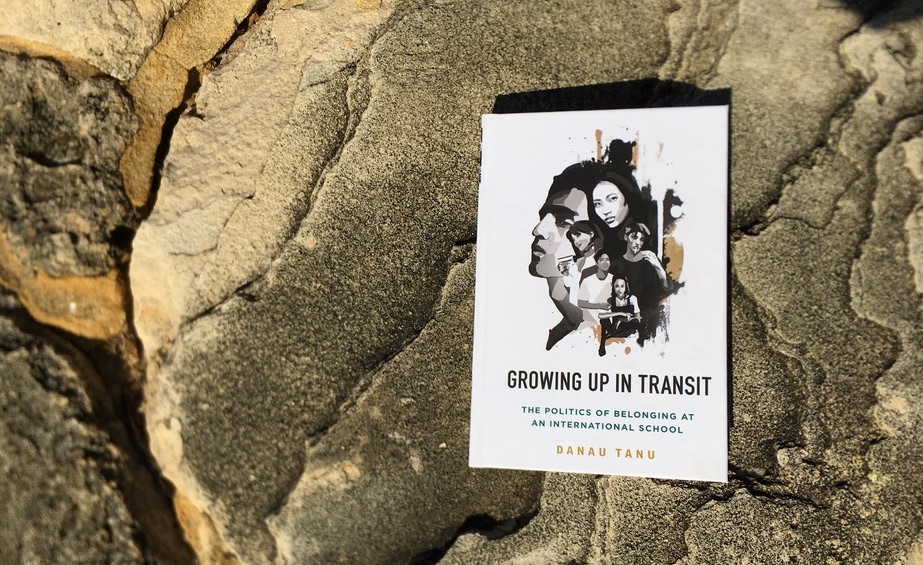

Danau Tanu, PhD, is an anthropologist and the author of Growing Up in Transit: The Politics of Belonging at an International School, the first book on structural racism in international schools. Available now in paperback. www.danautanu.com

Portions of this article first appeared in Growing Up in Transit, edited for this post. Pseudonyms have been used for all interviewees to protect their privacy.

This article was originally published in The International Educator (TIE Online) on 16 February 2021.

Related articles:

Osmosis: When children internalize racism through school (October 2020)

Strange Bedfellows (September 2020)